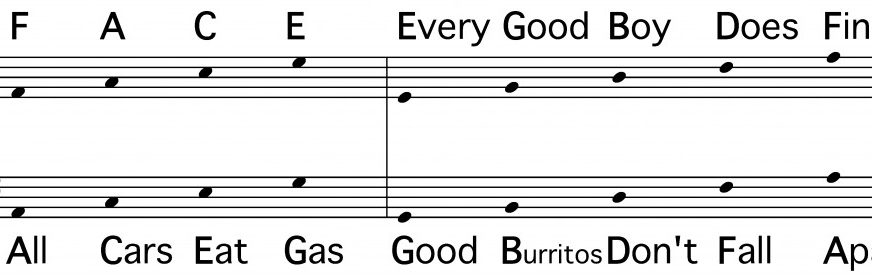

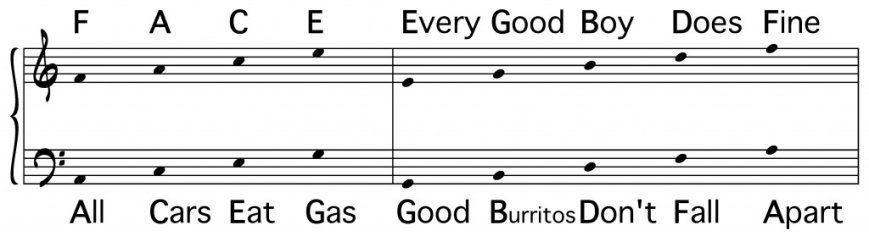

I’m sure most music teachers have taught students how to read music using rhymes at some stage. You know, Every Good Boy Deserves Fruit, FACE, Good Boys Deserve Fudge Always, All Cows Eat Grass – or whatever rhymes you have used.

This abstract way of thinking about notes is not only the slowest way to get to know musical notation, it is also highly unmusical, with the rhymes having no bearing on musical direction, pitch, or how each note relates to the next. When I first started teaching piano 10 years ago, I too taught note names in this way. I was rather naive and new back then…

I remember having a six year old who was very musical, practiced insane amounts of unnatural hours every day, and could read music exceptionally well. But if I asked her to name a note, or asked her to start from a certain note in the music, she wouldn’t know what I was talking about. I didn’t understand at that stage how she could read music so well without knowing her note names. Of course, she just knew which note corresponded to which key on the piano, without giving them names, and could follow patterns. When we’re teaching music as a language, however, being able to communicate verbally and have the same language is extremely important. And I believe knowing note names by their letter is very important. Otherwise, delving into more complex theoretical concepts and keys and scales becomes exceptionally hard as you can’t communicate verbally and be on the same wave length.

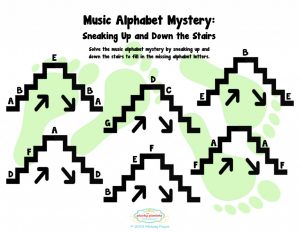

So when it comes to reading music, I teach following intervals and patterns first. I explain the lines and spaces and stepping up goes up the alphabet and coming down goes backwards. Rather than rhymes, becoming so familiar with the alphabet A-G that you can say it just as quickly backwards as forwards is key to getting to know notes. Then, all you need is a base point, say middle C for example, and you can figure any other note out from there, going up and down the alphabet. Every week I will give a student one other note to memorise – middle C first, then the bottom line of treble clef, then the top space of bass clef etc. So over time, they don’t have to work up or down too far from any one note.

Theory sheets such as the one below are very useful for students to put their alphabet practice into use. This one was obtained from The Plucky Pianista. Hal Leonard Theory and Notespeller books also have similar activities.

I get students to practice in two ways – one, of course, is saying note names as they play. I don’t think you can bypass this vital stage in getting acquainted with the notes – please, feel free to correct me if you feel this is wrong. Rather than rhymes, however, I get them using the alphabet up and down. The other way is just playing forgetting the note names, and following intervals. In the early stages, this is just steps (2nds) and skips (3rds), but as new intervals are introduced, rather than solely thinking of each note in isolation, trying to figure out its note name, showing shapes and intervals and how that relates to finger patterns and hand shapes on the piano is much more musical and relevant to understanding direction and phrases. This is, of course, how Hal Leonard introduces reading in their children’s method books. I also use this for teaching adults to read.

I have had a few students who have felt that if they don’t know the letter name of the note that they are playing, they think they are “cheating” or not really reading the music, and therefore try to just fumble through unmusically with lots of pauses, disregarding rhythm while they think of each note name in isolation, trying to remember which rhyme it was they needed for which clef. It has taken some effort with a few students to change this old way of approaching reading. Especially those who may have learnt in the past and are trying to remember how to read.

Taking this topic one step further, I then have students who feel if they are getting to know the music well and find that they’re not reading every single note, that again, they are cheating. I then ask them what is the point of the music on the page? The answer that I give them is that it is there to serve the purpose of creating the music. So once the music has served its purpose and you don’t need to read every note, that means that you’ve learned it well and the sheet music is then just a reference point as you need, or to see the bigger picture rather than individual notes. I often use the metaphor of reading. When you first learn to read, it is necessary to sound out each letter as you figure out the word. Now, we don’t even see individual letters, or even words, but read in sentences, unconscious of each letter. This has helped to put this into perspective for a lot of students. And this leads nicely into students starting to memorise. I find that it is when a student reaching a comfortable point in reading that they have this little panic about not actually being aware of the notes anymore. Only certain students have these worries. And it is generally the ones without a great ear or memory and have had to rely on reading heavily in the early days.

I would love to know any experiences other teachers have had with students and their reading ventures, or also any other methods of approaching teaching notation and reading note names. Please feel free to share (or to question my own methods).